Introduction

For me well know value investor that I look up to is Legendary billionaires like Warren Buffett

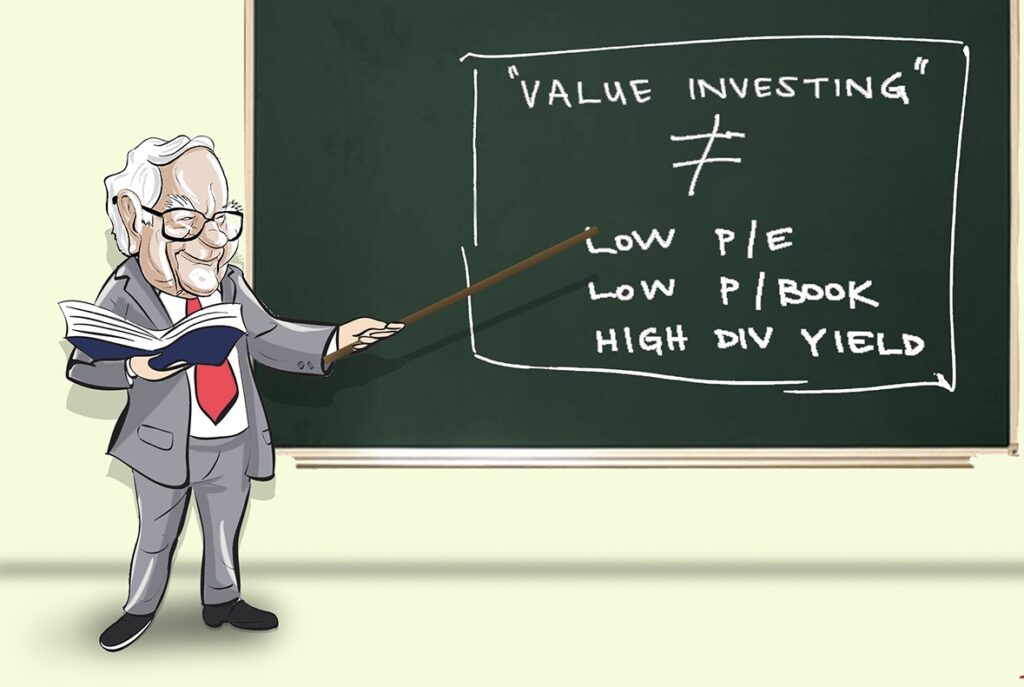

So what is value investing exactly? At its core, value investing means buying stocks that are trading at a discount to their intrinsic values – cheaper, in other words, than what your analysis says they should be worth. It basically involves trying to identify stocks that are “on sale”, exactly like you do when shopping for gadgets or clothing.

Value investing as a discipline was first developed in the 1920s by Columbia Business School professors Benjamin Graham and David Dodd, and was later popularized by their 1934 book Security Analysis. The pair are considered to be the fathers of value investing, and several of their students went on to become successful value investors themselves – most notably Berkshire Hathaway CEO Warren Buffett, the Oracle of Omaha (net worth: $100 billion).

Why value investing works

Value investing is a tried-and-tested strategy that’s netted many of its followers some seriously impressive returns. While that might be reason enough to convert you to the cause, it’s important to understand just why value investing works.

Begin by asking yourself the reasons why stocks sometimes become undervalued in the first place. In a market crash, for instance, panicking investors may indiscriminately sell all their stocks. As the saying goes, the baby gets thrown out with the bathwater – and shares of many fundamentally sound companies are left looking cheap.

Then there’s herd mentality. Investors often act irrationally and buy into things based on psychological biases rather than financial fundamentals. When they see a stock rising, for example, they tend to jump on the bandwagon – and when they see it falling, they typically rush for the exit. Such behavior is so widespread that it exacerbates both upward and downward moves, causing stock prices to dislocate from their intrinsic values and creating opportunities for the value-focused investor.

Overreaction to bad news is another reason why some stocks go on sale. The fact a company’s facing a short-term setback doesn’t necessarily mean it’s broken and won’t bounce back. The firm could end up selling the affected division and concentrating on other activity, say, or it might turn out to be a fuss over nothing after all.

Last but not least, some stocks seem cheap simply because they’re overlooked. Investors too often lust after sexy stocks that stand a chance of being the next big thing – to the exclusion of solid companies in less glamorous areas.

Key value investing principles

Intrinsic value

We’ve already touched on the first of three key principles: intrinsic value, or a stock’s “true” worth based on an investor’s analysis. A value investor will try to identify stocks trading at big discounts to their intrinsic values, buy them, and then sell them on for a profit after the gap between price and intrinsic value narrows.

So how do you go about estimating intrinsic value in the first place? This is more art than science, but the most theoretically sound method involves using a discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis. The idea behind DCF analysis is that a company’s value today is the sum of all its future cash flows discounted back to the present.

There are four steps to a DCF: 1) Estimate all of a company’s future cash flows; 2) Calculate the present value of each of these; 3) Add up those “discounted” cash flows to obtain a total value for the company; 4) Divide this by the number of shares outstanding to calculate an intrinsic value per share.

Margin of safety

As you’ll appreciate, there’s a lot of guesswork going on here – and end results can vary quite a bit. Value investors acknowledge their limitations when calculating intrinsic value, and for that reason they’ll typically only buy stocks trading at very big discounts to their estimates. That way, even if their figure for intrinsic value is over-optimistic, there’s still a good chance they’ve got the stock at a discount.

This big gap between a stock’s price and its estimated intrinsic value is the second key value investing principle: the margin of safety. Think of it as a risk cushion that minimizes losses should you turn out to be wrong. Benjamin Graham – one of the two fathers of value investing – only bought stocks priced at least a third below what he considered to be their intrinsic value. That was the margin of safety he felt was necessary to earn strong returns while minimizing investment downside.

Catalysts

After buying a stock trading at a sufficient discount, value investors then wait for the gap between its price and its intrinsic value to narrow. But that rarely happens of its own accord, which brings us to the third and final key value investing principle: catalysts. Absent one of these events, a stock might remain undervalued forever – and its investors disappointed.

One example of a catalyst is an acquisition. If a stock looks cheap enough but its business is fundamentally sound, then it could be an attractive takeover target for another company or a private equity firm. Any acquirer will likely pay a premium to the stock’s current price, allowing value investors to sell their shares at a level much closer to (if not above) their intrinsic value.

Another catalyst would be the company’s management team taking advantage of its too-low stock price to launch a share buyback program. Not only does this sound a note of confidence to investors, but reducing the supply of publicly available shares boosts the value of those that are left – again bringing their price nearer to intrinsic value.

There are many examples of catalysts, but here’s one more that might sound familiar: a company getting rid of a certain division. Say you’ve got a materials company with a fast-growing battery business but also a controversial chemicals factory. The latter might lead to some investors shunning the stock, causing it to trade at a discount. If the company then announces it’s selling off its chemicals plant to focus on batteries, its share price could end up rising closer to intrinsic value.

Let’s quickly recap those three principles above. Value investors buy stocks trading at discounts to their intrinsic values. That discount has to be big enough to provide a margin of safety. And value investors will usually only buy in if they believe there’s at least one catalyst coming up that’ll bring a share price more in line with intrinsic value.

How to become a value investor

Now you’re up to speed on the most important elements of the value investing philosophy, let’s explore three ways in which you can implement it in your own investing – ranked depending on how involved you want to be.

The hands-off approach

The simplest way to add some value investing flavor to your portfolio is to put some of your money in value-focused investment funds or exchange-traded funds (ETFs). Investment funds outsource all the hard work of stockpicking to professionals who invest client money according to a predetermined strategy – such as value.

You can search for funds – and screen for them based on specific criteria such as having “value” in the name – using free online tools like Investing.com (a global database), Morningstar.com (US), Morningstar.co.uk (UK), Portfolio Visualizer (US), and Trustnet (European). Once you find a likely-looking fund, be sure to go through its factsheet to learn more about its investment strategy.

Alternatively, you can invest in value ETFs. These are easier to access and cheaper, but unlike actively managed investment funds, ETFs are “passive”. They simply seek to replicate the performance of a given market index – in this case, one comprising what the index provider considers to be value stocks. That might mean low price-to-earnings or price-to-book ratios, among other things. You can use sites such as ETF Database to easily search for value ETFs.

The quantitative approach

Another way to gain exposure to value investing while keeping your emotions and behavioral biases out of the way is through quantitative (or systematic) strategies. Another benefit of these strategies is that they don’t require you to undertake deep analytical research into specific companies. One famous example, described by legendary investor Joel Greenblatt in The Little Book that Beats the Market, is called “Magic Formula Investing”.

Magic Formula Investing, a strategy inspired by value investing principles, begins by screening for inexpensive, dependable companies with a high earnings yield (operating profit / enterprise value) and a high return on invested capital (operating profit / ).

The idea is that you invest equal amounts in the top 30 stocks ranked by these criteria, rescreening and rebalancing once a year. This piece of wizardry, which starts off with a simple stock screen for high-quality value stocks, has – according to Greenblatt – consistently beaten the market.

The active approach

Our third and final approach is one for those who want to take things a bit further, doing their own in-depth analysis of companies like true value investors. This involves a number of steps.

First, you want to start off by screening for cheap-looking stocks. We suggest using Finviz’s online screening tool. It’s free and powerful, allowing you to filter things based on lots of different criteria. For example, one way to find value stocks is to select “low (<15)” under the “Forward P/E” filter. You can then play around with adding different categories. By way of inspiration, here are the ten things Benjamin Graham used to look for when picking stocks.

Once you’ve run your screen and have a shortlist of interesting investments, it’s time to pick a few for some further research. Looking at an individual stock, ask yourself: why is it cheap? Is it due to one of the potentially temporary reasons we discussed earlier (market crash, overreaction to bad news, overlooked stock, etc)? Or is there a more serious issue at play – such as the company being in an industry in terminal decline? You’ll probably want to stick to the former group.

If the stock’s got a good enough safety margin, then you may really be on to something. The final thing to investigate, of course, is whether you can foresee any catalysts in the near future that would cause the stock’s price to move more towards its intrinsic value. Could there be a potential buyer for the company? Does it generate a good amount of cash each year that it could use to buy back its shares? Or is there a business line the company would be better off without?

If a stock looks cheap for temporary reasons, is priced at a sufficient safety margin from its intrinsic value, and has a catalytic event on the horizon, then you’ve found every value investor’s dream. What are you waiting for?